Choosing Our Past in a Time of Genocide

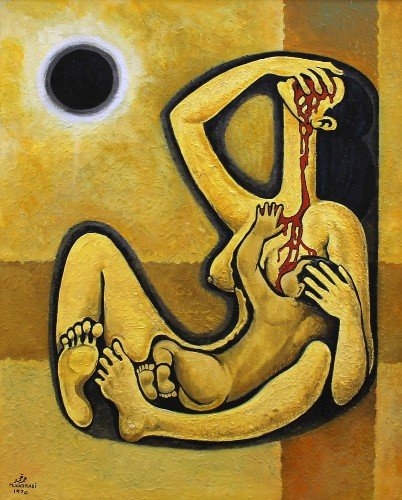

War Generation, Painting by Abdullah Al Muharraqi Oil on canvas, 127 x 100 cm, 1970

This talk was delivered at the Middle East Studies Association annual conference on November 25, 2025, in Washington, DC, as part of the panel marking “Fifty Years of Arab Studies: Identity, Knowledge Production, and Resistance at the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies.” The panel brought together Judith Tucker, Marwa Daoudy, Rochelle Davis, Fida Adely, Ziad Abu-Rish, Adey Almohsen, and myself. I was invited to speak from the position of a graduate student, reflecting on both the student experience and my own research at a moment of ongoing genocide and regional suffocation.

The invitation served as an opportunity for me to speak honestly about what it means to study, write, read and teach the Arab world under conditions of mass death, erasure, genocide, and political foreclosure. I took this charge seriously, and I did not approach the talk as an individual intervention alone. The speech emerged through sustained conversations with my cohort, with classmates whose work spans the region and whose thinking has been shaped as much by the street as by the archive. What follows reflects those consultations and the shared struggle to articulate what scholarship can and must do when the world it studies is under annihilation.

The version published here reflects minor edits for clarity and inclusion, made after discussion with colleagues and with attention to the plurality of political positions and analytical commitments represented within the field. Structurally, the text is deliberately broken into short paragraphs. Each paragraph is intended as a pause and a moment of holding before continuing. This was an orated piece, written to be spoken aloud, and its rhythm matters.

At its core, the talk is about inheritance — how it is chosen and how it is carried forward under duress. That emphasis remains intact, what has been edited has not been softened as I wanted to make sure that the stakes that animated the original speech remain the same.

I want to begin with Saidiya Hartman because her words touch something deep within the experience of studying the Arab world right now. And I quote her here:

She writes:

“Every generation confronts the task of choosing its past. Inheritances are chosen as much as they are passed on. The past depends less on ‘what happened then’ than on the desires and discontents of the present. Strivings and failures shape the stories we tell. What we recall has as much to do with the terrible things we hope to avoid as with the good life for which we yearn. “

That quote stays with me, especially as this genocide has unfolded.

To study and teach the Arab world, especially at this moment, has moved far beyond the familiar idea of scholarship as a career, or as a set of tools we acquire for professional life. For it has become a kind of longing.

A way of returning.

A way of holding close to the worlds we choose to come from.

At least for those in the field who still have conscience.

And sitting here with allies who feel this work just as deeply, I feel I can speak plainly.

Many of you know that this path we’ve chosen carries a weight. It’s heavy, but not hopeless. Emotional, yes, but not paralyzing. It asks us to study with our hearts open, even when those hearts are already bruised by what we’re witnessing.

In Washington, D.C. (of all places) Studying the Arab world has become a quiet form of resistance.

A space where we insist that our histories, our languages, our people matter.

That they are to be cherished.

That they deserve the dignity of careful, loving study.

That they deserve something gentler than the headlines.

But to understand why this work feels so urgent, we have to name the fragmentation our region is living through. The Arab world today feels scattered

Scattered in the political, geographical, and emotional sense. There is a sense of defeat humming underneath everything, a constant anxiety that creeps into our conversations even when we try to push it aside.

Our borders have hardened.

Our mobility has collapsed.

Our communities are being torn apart. And I mean that literally.

Yet studying the region has given us a way to understand this fragmentation differently. We’ve come to see the genocide not as a beginning or an end, but as one chapter in a long, painful colonial genealogy.

We know this is not the first rupture. Anyone who has turned a page in our history knows that. And when we talk about that genealogy, we talk just as much about the resistance and the moments of unity that have accompanied every act of violence.

We know this is not the first attempt to break us apart or redraw our maps or silence our voices. What is unprecedented today is the scale and spectacle of it. The sheer visibility. The unrestrained cruelty. And the celebration by our enemies of our mutilated bodies and children.

As the violence enacted on the Arab and colonized world has a history, so does our resistance.

That is something our foreparents have insisted on. Much of the written word by the native has pushed us to look backward,

to see how our parents, our grandparents, and the generations tied to them repaired themselves,

how they understood themselves,

how they built unity amongst themselves,

how they dreamt,

how they fought, and yes, how they faltered.

Their victories, their failures, their impossible decisions – this too is our inheritance.

And that is what Arab Studies, at its best, has centered for those who enter this field with conscience.

At its best, it has refused the racial and blood quantums of the colonial and Darwinian order,

this idea that Arabs must be one ethnicity, one purity, one lineage.

Instead, it has created a collectivity where the only condition for solidarity is consciousness. A consciousness that sees Palestinians as human, that refuses their dehumanization, that rejects their animal—————ification by the settler colonial project.

I see this consciousness that refuses categories in my own cohort. We are politically diverse, yet this consciousness has led us to converge on a few shared truths.

Whenever we speak of a free SWANA region, two words rise immediately: mobility and dignity, both for the region and for its people.

And maybe that’s what this discipline is shaping in us. I realized, as I was writing about the convergence of our perspectives, that studying here has created a sense of future-thinking rooted in the conversations we’ve carried with us from the street. We’ve become a generation that brings the Arab street (the SWANA street) into every archive and every classroom.

A generation that knows our work only matters if it serves the people who walk those streets, who endure those streets, who dream in those streets.

In writing this presentation, I sat with my classmates’ research and realized that the same street we keep talking about (the Arab street, the SWANA street) runs through every single project. It doesn’t matter whether the work is in Qatar, Amman, Beirut, Haifa, Cairo, Souss, or the Gulf. Each of us, in our own way, is trying to listen to the people who have been ignored the longest, the people closest to the ground, the people who feel every political shift first in their lungs and their legs.

You see it in the work on belonging, in Qatar’s classrooms where children learn how to stand in more than one world at once, and in Amman where Palestinian-Jordanian kids use their cameras to show us the corners of the city that let them breathe.

Or in the work on memory through the Rum Orthodox families who carry stories of the civil war because the state never did, and in young adults in Amman who negotiate family expectations that reflect deeper social exhaustion.

You see it in the confrontation with power: in the bandits and fugitives of late Ottoman Palestine, men criminalized for surviving amid collapsing social orders; in the British reshaping of Haifa’s port to control labor and movement; and in the retracing of Moroccan men recruited and taken from their villages and sent underground to work France’s coal mines during its post war reconstruction period.

Or in the work on care and religious life in Cairo, where Coptic aid workers navigate the state, donors, and faith all at once.

Or in the studies that widen our sense of region, from sovereignty in the pre-unification Gulf to the Gulf’s sports investments that Western narratives refuse to understand on local terms.

Each of these projects bends toward the same place,

each one listens for the street,

each one centers the people who inhabit it, endure it, shape it.

Identity, memory, agency, survival, sovereignty, imagination: they all begin there.

And my own work on dehealthification comes from that same place.

Because if my classmates are tracing how people belong, remember, move, work, worship, and resist, then my work follows what happens when even the right to survive those conditions is stripped away. When the street itself – its bodies, its clinics, its children, its breath – becomes a target.

De-healthification is born from that destruction,

from the evisceration of the Arab street in Gaza.

We sometimes use “the Arab street” as a metaphor for public sentiment, for a kind of popular political consciousness. But in Gaza, the street has been stripped of metaphor. It has been bombed, starved, amputated, eviscerated.

It has been denied medicine, denied hospitals, denied the possibility of repair.

It is vital to remind you all that the street is the place where life collects and prospers. Think of children running errands, neighbors exchanging news, elders sitting at their doors, moms exchanging dishes and recipes.

It is movement and memory and ritual.

It is where communities thicken.

And when you cut off medicine, when you close the hospital, when you confiscate ambulances, when you deny electricity, when you criminalize care itself,

you are destroying the street by other means.

There is a logic to this. A method.

Colonial states do not fear the hospital because it is a building servicing the natives.

They fear the hospital because it keeps the street alive,

because repaired bodies can resist, can return, can organize, can remember.

When you dismantle healthcare, you dismantle the possibility of return.

And what I’ve tried to do in my own research is narrate this method,

I’ve tried to name it,

track its evolution. Because Gaza did not become unhealable by chance or misfortune – this was a design,

year after year, policy after policy, permit after permit. The destruction was slow before it was spectacular,

it was administrative before it was aerial,

it was bureaucratic before it was ballistic.

And if this is how a legitimate settler-colonial state treats Palestinian health under the cover of law and diplomacy, then we have to recognize the implications.

This violence does not end at the walls of Gaza. Israel’s frontier is always expanding, and the methods used to biologically throttle Gaza—sabotage, denial, dependency, obstruction — can be exported,

normalized,

and echoed in other Arab capitals if we fail to understand them as a coherent system.

In a moment like this, studying such destruction is both unbearable and necessary. It is a way of witnessing when the world prefers silence. A way of refusing the lie that this violence is sudden or inexplicable.

And through all this,

through our research,

our grief, our disagreements,

we found community. Even in despair, we formed something collective,

Something quiet and steadfast.

This is, in many ways, exactly what the founders of this Center imagined. Hanna Batatu, Hisham Sharabi, Michael Hudson, the whole lot, their project was to build a place where we, the critical and compassionate, have a refuge. A place where Arabs and those committed to the region could think, speak, write, argue, imagine, without shrinking themselves,

a place where the region’s stories could breathe.

And today, in a time of genocide, that inheritance feels even more alive. Because the world outside is breaking, and somehow, in this small corner, we are still learning how to imagine.

Hartman asks: From the holding cell, was it possible to see beyond the end of the world and imagine living and breathing again?

I think, quietly, my cohort and those thrust to narrating the region's erasure are answering that question. With our research,

with our care for one another,

with our refusal to let the past (or the future) be chosen for us.

This line of work has no certainty, nor is it an escape. But it’s given us the chance to be courageous by taking up space to keep imagining and believing that despite the fracture and pain, we can still choose our past,

and therefore choose our future.

Thank you.