Resisting Necropolitics: The Art of Death in Palestinian Resistance

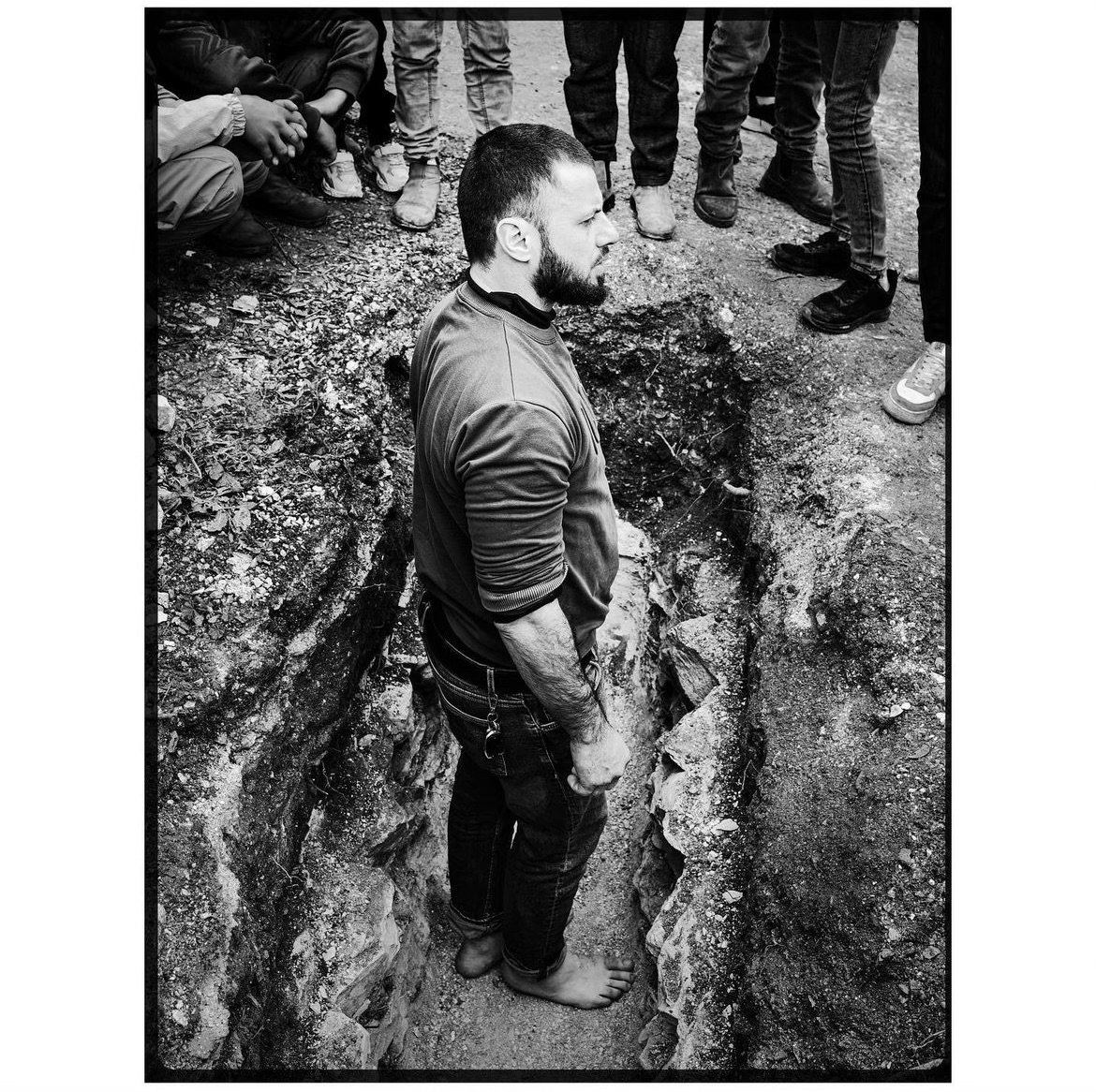

“قبر الشهيد” - The Martyr’s Grave

Photo taken by Sakir Khader, retrieved from@sakirkhade

Introduction

Death, a timeless and inescapable facet of the human condition, has long yarned the hearts and minds of artists, writers, and truthbearers, weaving its way into the tapestry of art, literature, and the psyche of those dehumanized throughout the annals of the hegemonic history. Death has been a subject of profound pain, mourning, reflection, and jubilation. Yet, when viewed through the prism of necropolitics, death takes on a complex guise - one intricately interwoven with power, politics, and defiance. Coined by the visionary Achille Mbembe, necropolitics encompasses the mechanisms by which states, and regimes assert domination over the lives and deaths of the populace under their control, often through tyrannical and dehumanizing edicts.[1] By delving into the complex interplay between necropolitics and the concept of death, a nuanced understanding emerges of how communities respond to the deceptive tactics employed to manipulate their lived and mortal experiences. Within this framework, two distinct avenues come to light - one tainted by dehumanizing rhetoric dictated by colonial powers, and the other, often overlooked, shining a spotlight on the agency of the oppressed as they forge a collective, innate resistance against the terms imposed by oppressive regimes. To truly grasp the profound nature of this collective resistance, one must view communities that defy the oppressor's narrative control over both body and soul as a catalyst for uncovering art in death. Over the last month, I’ve studied necropolitics and how it has shaped Palestine in order to understand how Israeli policies compel Palestinians to redefine death as a contradictory union of tragic action and, death as an eloquent memory where heroes are born to transcend from individuals to community icons. My aim has been to pay homage to the Danticatian[2] method of extracting and highlighting the art in death, an art sculpted, brushed and curated by communities and individuals who are temporarily ravaged by the nuances that death and life brings to this world.

The Smile

I don’t know Mohammad Daabas but when I first saw his smiling face plastered on every wall in Nablus during my visit in December 2022, my thoughts flashed to feel that I’ve known this person all my life. Mohammad seemed like a happy young boy whose infectious smile could capture your heart and cast a charming spell. Born and raised in Nablus, Jabal al-Nar (Mountain of Fire), Mohammad was a 13-year-old who attended a protest against an Israeli settlement expansion, where he was shot in the head in what many called a field execution.[3] His martyrdom deeply affected the morale of Nablus, and indeed all of Palestine. The innocence he embodied in the public consciousness, captured in the images that still linger six years after his cold-blooded murder, have become a powerful symbol of Palestinian unity.

For me, Mohammad represents every community in Palestine. I see him in the face of every grieving mother who watches as her son is buried in the ground, in every father and brother who solemnly carry their loved one's corpse to the cemetery, where a collective goodbye is held to honor and bid farewell to another fallen hero on their journey to God's realm, in every young girls face who feels robbed of her protector, her guidance, her motivator. The Mohammad I am familiar with are individuals that have traversed the pages of history books and testimonies about what has transpired in Palestine since the British Occupation in 1917.

While I may not have personally known Daabas, I am acquainted with the Mohammads in every part of Palestine - the Mohammad of Jaffa, the Mohammad of Galilee, the Mohammad of Akka, the Mohammad of Nablus, the Mohammad of Jenin, the Mohammad of al-Quds, the Mohammad of Tulkarm, the Mohammad of Haifa, of al-Khalil, of Nazareth, of Bethlehem, and the Mohammad in exile. Mohammad's death, and the unwavering efforts to ensure his presence is felt, remembered, and commemorated, serve as a testimony that while human beings may come and go, the memory of those who have died for the land transcends place and time, becoming eternal icons in the struggle against oppression.

The symbol that blossomed into an iconic membrane of youthful resistance to occupation and colonialism by the commemoration of Mohammad Daabas was his wide innocent smile in the face of injustice and cruelty. The smile soon after his death rapidly spread onto the faces of other young Palestinians, when faced with cameras, during moments of detainment, being knelt on or violated. For Palestinians, Mohammad’s smile was serene, as if they had glimpsed a world beyond our mortal realm, a realm where pain and sorrow were but distant memories. It was a tranquil smile that spoke of innocence lost, a reminder of the fragility and ephemeral nature of life itself and a testament to the human capacity for hope in the face of despair. It was a poignant reminder of a stolen childhood, a fragile yet powerful expression of resistance in the midst of occupation. Mohammad’s smile metamorphosized from a child robbed of his childhood to a symbol, an idea, that to smile is to defy the odds in living a life free from oppression and necropolitics. As the late and powerful Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish once reclaimed “those who face freedom with a smile” are worthy of the people’s applause.[4] May God rest Mohammad’s soul and allow his family to find comfort in the spark he lit into the minds of young Palestinians.

Necropolitics

The plight of modern-day Palestine is a glaring example of the treacherous impact of settler colonialism. Through a necropolitical lens, one can begin to comprehend how institutional powers have wielded control over the lives of those deemed undesirable, exerting direct authority over the fate of the living and the dead through a complex web of disciplinary, biopolitical, and necropolitical mechanisms. As aptly stated by Achille Mbembe and Judith Butler, settler colonial regimes have historically reshaped the body through politics, transforming it into a battleground for redefining the power dynamics between the colonizer and the colonized.[5] Mbembe analysis is important to highlight as he argues that the power entrusted by the newly settled population through settler colonialism has bestowed upon them the "ultimate expression of sovereignty," enabling power brokers to wield their authority by dictating who is allowed to live and who must perish.[6] Within this exchange, the colonized are then valued as a ‘bare life’ – a term that identifies as a life exposed and integrated into a structure that places exceptions – allows killing to become a legalized spectacle for the colonial through the suspension of the law, which in term shapes the psyche and exposure that the colonised has with death itself.[7] In the turbulent landscape of Palestine, the mechanisms deployed by the Zionist regime to exert control over the deathly processes and experiences of those under its dominion are glaringly evident.

Through a thought-provoking study conducted by Daher-Nashif (2021),[8] readers were presented with a harrowing glimpse into the conditions placed on onto Palestinian families who bear the brunt of Israel's body confiscation policy. This policy involves Israeli soldiers cruelly stealing the corpses of deceased Palestinians and imprisoning them in ice boxes, as a means to further punish and humiliate grieving families. Such agonising practices highlight the lengths to which the Zionist regime goes to control and manipulate the very process of death, perpetuating a cycle of oppression and indignity onto the Palestinian people. Throughout history, the practice of obscuring Palestinian burials has been a brutal and deliberate tactic employed by occupation forces. Traces of such practices go as far back as the late 1960s, where Israeli soldiers routinely buried Palestinian bodies in undisclosed areas without the knowledge or consent of their families. What is further dehumanizing is how the state would designate bodies only by impersonal area codes and identification numbers – similar tactic deployed 30 years earlier in Nazi Germany.[9] Disturbingly, it has been reported by various NGOs that many of the burials took place in four cemeteries located within Israeli borders, which enabled an ongoing system of requiring Israeli sanctioned permits for family members who seek to visit their deceased loved ones. The torment and disrespect inflicted upon the bodies of Palestinians reached a new level of cruelty in the 21st century, when Israel's Public Security Minister, along with Prime Minister Netanyahu, approved the heinous act of withholding Palestinian corpses and placing them in freezers as a show of force and to inflict anguish upon mourning families. Many of the families were required to wait anywhere between 20-100 days before receiving the body of their loved one.[10]

State Defined Death

As Daher-Nashif poignantly points out, Israel's fetishization and obsession with controlling the Palestinian people is fully displayed in how it manipulates the release of frozen corpses. The state conditions its approval of funeral processions, dictating a limited number of visitors, conditions the timing of the burial to be at night, bans any traces of cellular devices, and occasionally mandates the requirement of military personnel presence at sanctioned events that mourn the martyred. Even in death, Israel exercises its oppressive power, further dehumanizing and disrespecting the Palestinian people in a flagrant display of necropolitical domination. The long list of requirements imposed by Israel on the occupied Palestinian people is a stark reminder to Susan Abulhawa's distressing excerpt from her book "Mornings in Jenin." Mandating military attendance at funeral precessions is arguably the most daunting, Abulhawa exposes readers to the lingering trauma and internalized suffering that Palestinians endure in the presence of occupation soldiers who dehumanize and cannibalize the Palestinian body and soul in their relentless pursuit of land theft and ethnic erasure. Through Amal's heartbreaking description of losing her father in a brutal and hasty manner, the reader is a witness to how the influence of death and occupation impacts the Palestinian psyche, and the defiant response that Palestinians have in rejecting the weak state that the Israeli regime tries to impose upon them. Amal's observations, as she sets eyes on her mother in the presence of soldiers in a makeshift hospital after the 1967 war, are crystal clear in capturing both the natural reaction to seeing your killers in plain sight and the rejection of the deathly influence and occupation on the Palestinian psyche. Her words speak volumes:

She sat motionless in a corner, just as I had seen her sitting on the ground when I had stood up in the kitchen hole. I stopped. Her spacious empty eyes did not see me standing before her. She seemed to see nothing. "Mama." I touched her lightly, but she did not respond. I put my face in front of hers, but her eyes looked through me. Sister Marianne approached me….”do you know this women?”“Is she dead?". "No, dear, She's in shock”

Do you know her?" Sister Marianne asked again. Just then, a beseeching resentment filled me. I hated Mama for being in shock, whatever that was…"No," I lied. "I don't know her." I shrank behind my disgraceful lie to remain in the protection of Sister Marianne… [11] What stands out in Abulhawa's depiction is her courage in making the readers confront the immense pain and reactions that Palestinians endure in the face of death, while also illustrating their unwavering refusal, no matter how raw it may seem, to succumb to the Zionist aspiration of completely shattering the Palestinian spirit, even after death. Amal's deliberate distancing from her distraught mother serves to highlight both the steadfast resilience of Palestinian resistance to Israel's psychological control and the strides needed to be made in building a future that prioritizes healing the psyche of those who have lost in the battle against oppression, as well as those who have triumphed. This distancing also underscores Abulhawa's keen understanding of the Israeli state's colonial tactics of divide and conquer, aimed at undermining Palestinian cohesion through domination and resistance. A response to the exposure of Israel’s conquers and divide has been a tightening sense of collectivity by the Palestinian populace.

Collectivity in Death and Resistance

After 75 years of Israel's relentless efforts to exert control over the land and its people, Palestinians have learned to navigate the complex challenges that arise in the wake of death by emphasizing collective participation in assisting the deceased. Daher-Nashif's interviews highlight the unity that Palestinian families displayed in 2015 as they waited for the release of their loved one's body. Themes emerged that revealed how the struggles against these barbaric policies were not limited to just one family but were collectively experienced by the entire community. Among the interviews, there was an emphasis on the nature of the collective which manifested in rebuking a sense of dejection expressed by many when discussing the obstacles, they faced in giving their loved one a proper farewell. The father of Omar, a prisoner held for 50 days without burial, explained:

When the corpses were detained, we made a sit-in tent near the Red Cross in al-Khalil. We were 19 families from al-Khalil; we sat in the tent for 24 days. The whole day. We did demonstrations, we wrote to the UN, to the foreign media and to all the media [outlets] asking to have the bodies back. Israel tried to convince us to get them [during] the night and bury them under conditions, but we were strict and refused these conditions. We wanted to bury them during the day in funerals of martyrs (Daher-Nashif, p.953)[12]

Notions of Martyrdom in Palestine are like a canvas painted with unique hues, shaped by the land's history and the social conditions that have ravaged it for the past 75 years. Elicited from Abu Omar’s testimony are an understanding that anyone who falls victim to murder by the Zionist regime, whether as a civilian or a resistance fighter, and does not betray the cause of liberation, is bestowed with the revered status of martyrdom. The names and faces of these martyrs are etched in the collective memory, elevated to the status of champions who bravely faced the occupation with the tools of the oppressor.

What is even more intriguing and deserving of artistic contemplation is how martyrdom in Palestine has evolved into a state to be achieved, a quote-unquote nirvana that symbolizes a resolute push against the ongoing struggle and an infiltration of the Israeli psychological warfare. To be martyred in Palestine is to ignite a fiery fight within your immediate community against the Zionist oppressors, providing ammunition for your family and friends to forever remember that the occupation is neither sustainable nor livable, despite the privileges it may afford to the elites within your community. The concept of martyrdom has become a powerful form of artistic expression, capturing the indomitable spirit of resistance and resilience that continues to thrive in the face of adversity in Palestine.

We can see the spirit of martyrdom is evident in the celebratory nature that takes hold in the funeral precessions. In Lisa Franke’s own words, the funeral becomes a “Palestinian Wedding. Recontextualized in texts glorifying the martyrs”.[13] Death in Palestine is thus mythicized to ensure it is mourned as a moment free from sorrow, a way to celebrate death as a sacred wedding ceremony, where the departed soul is forever betrothed to the land. It is a profound and powerful belief that reflects the indelible bond between the Palestinian people and their beloved homeland, where martyrdom is not an end, but a timeless union, symbolizing a profound commitment to resistance and liberation.

An Understanding to Death

Delving into the study and contemplation of death is a formidable endeavor. It spans across disciplines, from sociology to philosophy, history to theology, with diverse perspectives seeking to unravel the enigma of life's greatest mystery. Among the Western thinkers who have grappled with this profound subject, Paul Tillich's insight resonates deeply with the Palestinian understanding of death. Tillich's probing question, "If you cannot accept death, can we really live?",[14]unearths a buried truth: that to truly live, one must embrace and cradle death as an inevitable destination that all will inescapably reach. While on the other hand mainstream Western philosopher hold quite a different understanding. La Rochefoucauld’s analysis where he opined that humans "cannot look directly at either the sun or death,"[15] and Paul Ramsey’s argument against stripping death of its inherent nature by stating that "true humanism and the dread of death seems to be a dependent variable",[16] both highlight the dominating perspective held by Western philosophers. In rebuking this stream of knowledge, after studying death in Palestine, I find that the failure for Western theorists to acknowledge the privilege they hold in terms of choice and the suffocating impact of necropolitical policies on racialized and colonized populations hinders their ability to see other perspectives on the subject matter. Populations under similar social and political conditions as the Palestinians are forced to confront the lived conditions that shape their understanding of death, which forces them to arrive at their own conclusions based on the stark reality and frequent presence of death in their communities, rather than on mere fear and rarity of death as seen in the West. Theorists in the field of death often lack the lived and experiential knowledge that places necropolitical policies at the forefront of how communities analyze and construct their own understanding of death. For Palestine death is seen as act of imagination, resilience, resistance, and a tool that we put on the line for the liberation of our homeland. The embrace of death as a part of our struggle is born out of a lived reality that is shaped by necropolitics and the need to resist oppressive forces in order to reclaim our dignity and freedom.

May God rest and bless those martyred for Palestine and liberate the homeland from ideologies that find contentment in manipulate humanity for its own political and economic agenda.

Footnotes:

[1] Mbembe Achille (2003) Necropolitics. Public Culture 15(1): 11–40.

[2] Danticat, Edwidge. (2017). The art of death : writing the final story. Graywolf Press.

[3] Boxerman, A. (2021, November 5). Thirteen-year-old Palestinian said shot dead by IDF in

clashes near Nablus. The Times of Israel. Retrieved April 15, 2023, from https://www.timesofisrael.com/thirteen-year-old-palestinian-said-shot-dead-by-idf-in-clashes-near-nablus/

[4] Darwish Mahmoud, (2013) Unfortunately It Was Paradise: Selected Poems, trans. and ed. Munir

Akash and Carolyn Forché, with Sinan Antoon and Amira El-Zein. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 6.

[5] Daher-Nashif, Suhad. (2021) “Colonial Management of Death: To Be or Not to Be Dead in

Palestine.”Current sociology 69, no. 7. 945–962.

[6] Mbembe Achille (2003) Necropolitics. Public Culture 15(1): 11–40.

[7] Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer : Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford, Calif: Stanford

University Press, 1998.

[8] Daher-Nashif, Suhad. (2021) “Colonial Management of Death: To Be or Not to Be Dead in

Palestine.”Current sociology 69, no. 7. 945–962.

[9] “Tattoos And Numbers: The System Of Identifying Prisoners At Auschwitz.” United States holocaust memorial museum., 2019. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/tattoos-and-numbers-the-system-of-identifying-prisoners-at-auschwitz.

[10] Daher-Nashif, Suhad. (2021)

[11] Abulhawa, S. (2010). Al-Naksa. In Mornings in Jenin (pp. 73–74), Bloomsbury.

[12] Daher-Nashif, Suhad. (2021) Page 953

[13] Dehghani, S., Saad, H.-A. S., & Franke, L. (2014). The Discursive Construction of Palestinian istishhädiyat within the Frame of Martyrdom. In Martyrdom in the modern Middle East. Page 193.

[14] Pinter, Harold. (2005). Death etc. Grove Press. Page 103

[15] Ibid page 102

[16] Ramsey, P. (1974). The Indignity of “Death with Dignity.” The Hastings Center Studies, 2(2),

47–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/3527482